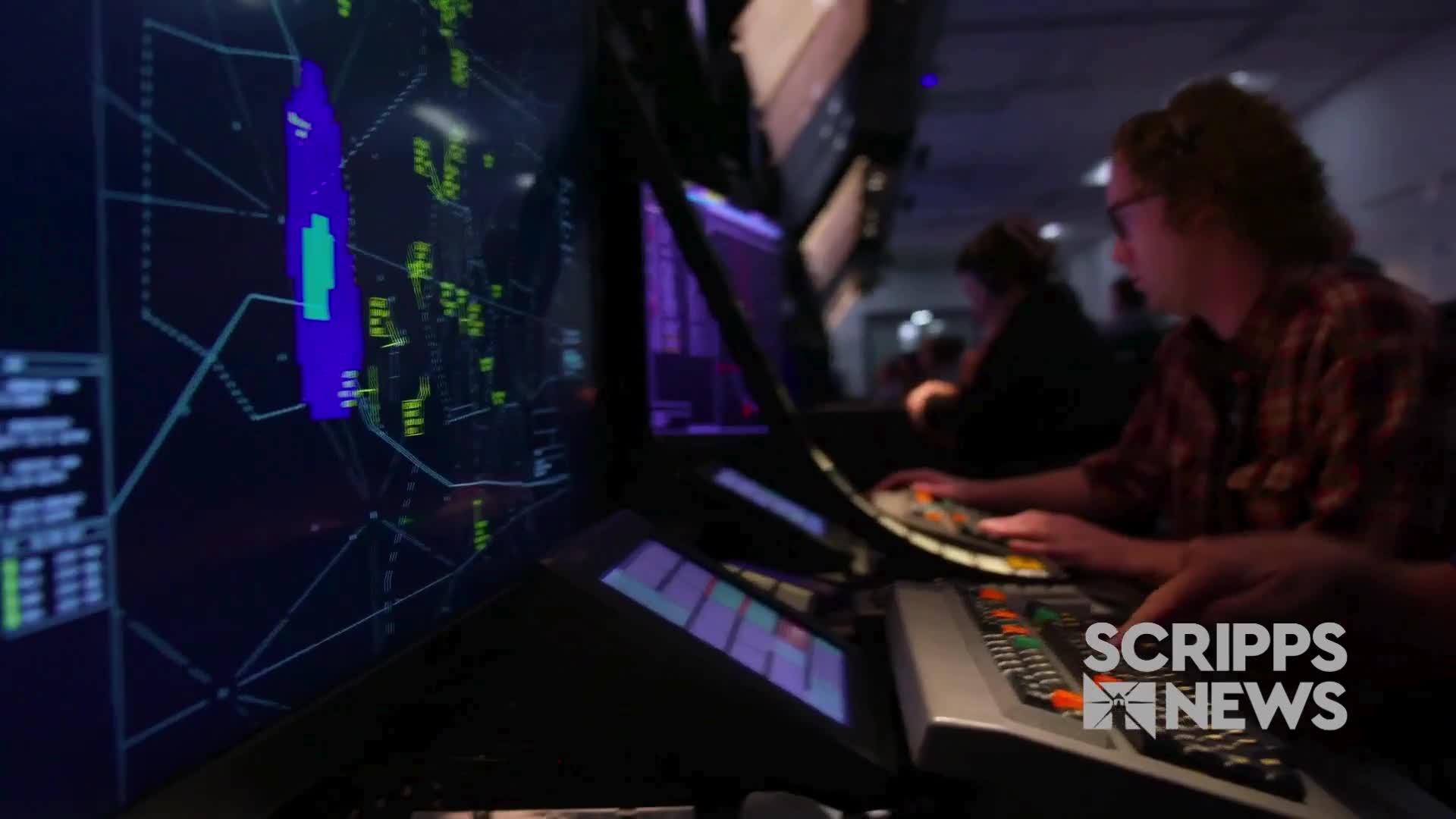

In a dark noisy room in Oklahoma, air traffic control trainees hunch over radar screens as they track planes flying through congested airspace in the Deep South.

They are flights that don't actually exist, part of a simulation to see how students handle the pressure of working in a real control tower.

"As close to as realistic as we can get," said Alan Stone, air traffic training branch manager at the FAA's training academy at the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City.

This is where the FAA is schooling its largest class ever of air traffic controllers. The agency agreed to let Scripps News inside for a rare peek at the intense process of learning how to keep planes safely separated in the sky and on the ground.

WATCH | A closer look at training for sky safety

Too few controllers and outdated equipment caused days of delays this spring at Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey. In January, a deadly mid-air collision of an army helicopter and American Airlines flight in Washington also drew attention to a chronic shortage of air traffic controllers that goes back years.

There are about 11,000 certified controllers nationwide with a need to hire about 3,000 more, according to the FAA.

An inspector general's report shows 20 out of 26 critical locations were classified as under-staffed.

Under the Trump administration the FAA has streamlined hiring, bumped up starting pay by 30 percent and offered a bonus for those willing to work in remote areas.

The FAA announced a goal last year of hiring 2,000 new controllers in 2025.

"I remind people we didn't get here overnight, so we're not going to get out of the situation overnight," said Chris Wilbanks, vice president for mission support for the FAA's Air Traffic Organization.

"If you want to be an air traffic controller the demand is there," he said. "You'll come right through the beautiful state of Oklahoma and spend anywhere from two and a half to three and a half months out here doing the training."

President Trump's big domestic policy bill just passed into law includes $100 million new air traffic training technology, but much of the instruction tools at the academy are far from high tech.

To model takeoffs and landings, new trainees on headsets guide toy airplanes around a tabletop airport.

"This gives the students the first opportunity to take all the information that they receive in academics and actually use it," said Chris Fairbanks, a contract instructor.

Students during the exercise are also learning how to speak clearly and confidently, Fairbanks said. It's known as controller voice.

"What I tell the students is say it like you mean it and stick the landing," Fairbanks said.

ADDITIONAL REPORTING | Federal incentive program aims to address air traffic controller shortage

Only a small percentage of applicants qualify to attend the academy after passing a tough written test and going through a medical and background check. Many won't make the final cut when instructors watch them handle the kind of stress I was able to experience first-hand in a control tower simulator.

With the help of an experienced controller and a script of what to say, I begin giving commands to a small fictitious Cessna preparing to land at an airport in front of me on video screens.

"Enter left, downwind runway 2-8 left," I say, reading the script.

"You nailed it," says Eric Wedel, the instructor over my shoulder.

Keeping track of one plane was hard enough.

Then came more. The nonstop computerized voices of pilots request approval to take off and land at the airport.

"You're talking to two and you're looking at three," Wedel says.

Even with a radar screen, I'm told to rely on my eyes to constantly scan the "sky." A controller next to me sends over one of the paper strips used to keep track of flights.

"Ground gave you a strip for a departing aircraft," Wedel says. It is a fourth plane.

"You're not talking to them yet so don't stress just yet," he says.

The immense focus required and high stakes help explain why it takes years to certify controllers. Those who graduate from the academy will continue practicing in real control towers before being allowed to work on their own, a career that pays a six-figure salary.

It's the rare job where artificial intelligence is not seen as an alternative in the near future.

"I think you're always going to have to have the human in the loop separating the airplanes," Wilbanks said. "It won't be in my lifetime that we will have A.I. clearing someone for takeoff."